This year I visited Vienna thrice, each time for different reasons and circumstances. On all three visits, I did not miss the opportunity to explore the extraordinary art and intellectual spirit of Vienna of the beginning of the 20th century. In May, my cousins Dotty and Ruthy accompanied me to visit the Albertina Gallery, in June I enjoyed the Belvedere Museum, and now in November with my wife Vicky, we went to see the Leopold Museum, focused on Klimt, Schiele and Kokoschka.

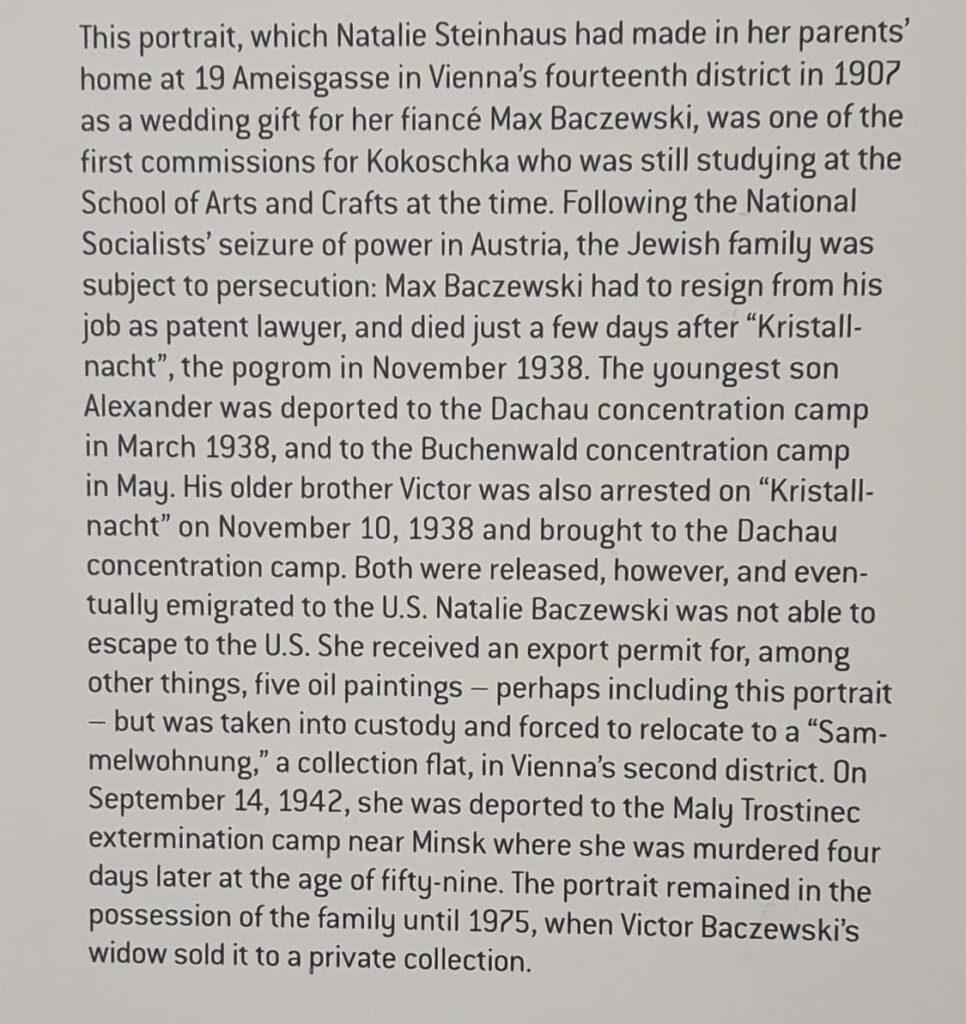

We eagerly approached the Kokoschka collection, where we were greeted by the portrait of a young, attractive, dark haired lady in a burgundy dress, sitting against the dark backdrop of an interior. Her large, dark eyes look intently at us; her subtle smile, slightly parted lips and her relaxed sitting position with her crossed arms, express her complacent mood and the affection with which she poses for her portrait. The artist’s rough brush strokes expertly render her elegant dress with satin, semitransparent sleeves and collar, the few details of the chair she is sitting on, a vase with an intriguing, bright medallion and other details of the interior, presenting her as a bourgeois, well to do woman. Kokoschka has magically converted the canvas into a very real and beautiful person with unequivocal wit and character.

I was totally taken aback when, after beholding the portrait, I stepped closer to read the explanatory text, and saw the lady’s name: Natalie Baczewski. I know this name, I exclaimed to myself. This was not some anonymous Viennese woman; the portrait was of none other than my mother’s aunt!

Very excited I continued to read the text. Natalie, born Steinhaus, commissioned the young art student Oscar Kokoschka to paint her portrait in 1907 as a wedding gift to her fiancé, Dr. Max Baczewski. This was one of Kokoschka’s first commissions. Thus, I learned that I have a family connection with one of the Viennese Jewish women patrons of the arts of that epoch, who modelled for and commissioned paintings from artists who were already or would eventually become world famous. I also learned of her tragic demise 35 years after posing for the portrait.

The astonishment of my encounter with Natalie was so great, that I was unable at that moment to retrieve from my memory any previous information I possessed about Natalie. After discovering the portrait and reading the explanatory text, my wife and I took a rest over a cup of coffee at the museum cafeteria. After I came around somewhat from the excitement, one by one, I started to recollect isolated bits of knowledge I had previously come across about Natalie:

Natalie's parent's house, as I learned from the portrait's explanatory text, was on Ameisggasse in an affluent neighborhood near Schoenbrunn palace. Her sister Rosa, with husband and two children – one was my mother – lived on Einwanggasse, literaly around the corner.

My late mother spoke to us about her aunt Natalie, the mother of her favorite childhood cousins, Xander (Alexander) and Victor Baczewski, whom she mentioned frequently, always with affection. Xander's son was Tony Barczewski from the USA, whom we befriended when he lived for a few years in our home city of Bogota. We had first met him, his mother and his wife at a family reunion in California in 1998.

In 2002, my mother found a historic photo, with many members of the Steinhaus’s, her mother’s family, on the occasion of the wedding of one of her cousins. My mother sent me the photo with an attached, transparent overlay legend and a detailed, handwritten explanation of who many of the persons in the photo were. My mother, her parents, Natalie, her husband and two sons, amongst other relatives, appear on the photo.

Many decades ago when I was in my late teens, my parents took me on a trip from our home in Colombia to Austria. Natalie’s son Victor also happened to be visiting there from the USA with his Swedish wife Birgit. We met them at Hallstatt, a medieval village set dramatically on the shores of a lake surrounded by towering Alps. I remember my mother’s excitement at meeting her beloved cousin. But his extroverted wife took center stage at the get-together, limiting their possibility to catch up, causing my mother much frustration.

As I mentioned, I had also visited Vienna last May. My cousins Dotty Altmann and Tony Friedmann, (another cousin, not Baczewski) took me to see the “Remembrance Stones” of an ancestor victim of the Nazis. I saw the elegant and centrally located building and read the name Natalie Baczewski engraved in the bronze stones embedded in the sidewalk pavement. For me at that moment, that visit was not more than an interesting and sad encounter with one of my several ancestors who were victimized during the holocaust.

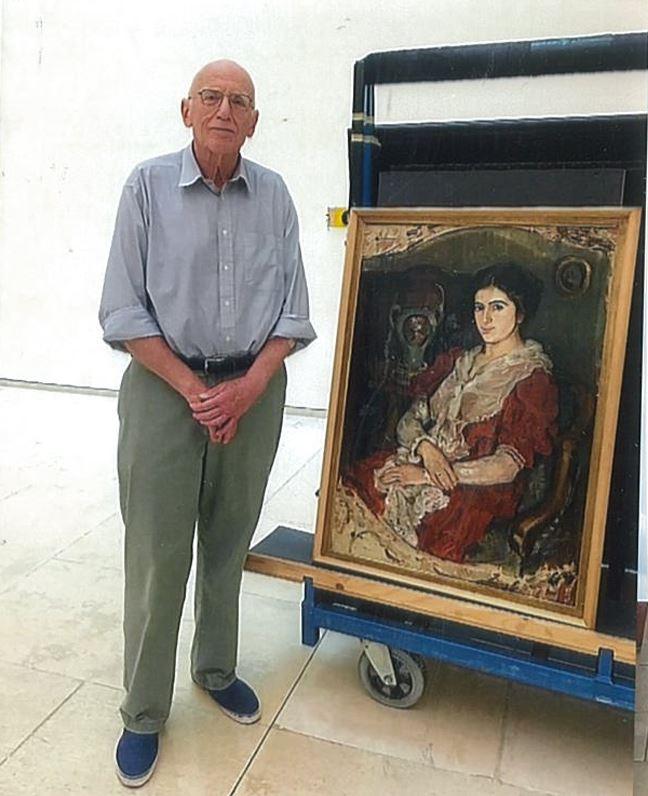

In 2020, I was included in a chain of email messages from Natalie’s grandson Tony Baczewski (mentioned above) and his wife Judy Vasos, a genealogy detective. The emails describe their trip from California to Vienna for the ceremonial placement of a commemorative “Remembrance Stone” on the sidewalk next to Waltergasse 4, the last building where Natalie lived as a free human being. On that trip, Judy and Tony saw the Kokoschka portrait in a storeroom of the Leopold Museum, since at that time it was not on exhibit. My cousin Dotty wrote that her father, my late uncle Felix, knew of the existence of the portrait, and assumed it was very valuable, but the family had lost track of it. Birgit, Victor's widow sold the portrait to a private collector in 1975. Judy wrote a beautiful, handwritten book about their revealing and emotional trip to Vienna, and about what they had learned about the tragic last years of Natalie's life:

After the Nazis expelled Natalie and her family from their home on Waltergasse, they confined her to a “collection flat” where she was "stored" in what must have been unspeakable conditions during 4 years.

My immediate family and other relatives – over 20 persons – were spared from the horrors of the holocaust, thanks to my father’s foresight and his proactive emigration from Austria in 1936, two years before Hitler annexed Austria, and thanks to the safe haven Colombia offered them. Natalie arranged to join her sons in the U.S., but in the end was unable to escape from Nazi Austria. Following 4 years of horror, the Nazis brought her to Maly Trostinez extermination camp in today’s Belarus on September 14, 1942, and, after 4 days, undoubtedly of unspeakable suffering, was murdered on September 18. On September 16, 2 days before her death, her niece Lore – my mother – on the other side of the Atlantic bore her first child, Tommy.

At the Leopold Museum cafeteria, digesting my unexpected encounter with her wonderful Kokoschka portrait, all these isolated, in my mind disconnected bits of information about Natalie suddenly and very powerfully came together.

Natalie suddenly become a part of me. I now feel unequivocal affection towards her. She moves me. She lives in my mind, in the same neighborhood where my dear mother and father live. Natalie’s tragic fate now does indeed bring tears to my eyes.